ESSAYS OF MONTAIGNE

UPON SOME VERSES OF VIRGIL

BY HOW much profitable thoughts are more full and solid, by so much are they also more cumbersome and heavy: vice, death, poverty, diseases, are grave and grievous subjects. A man should have his soul instructed in the means to sustain and to contend with evils, and in the rules of living and believing well: and often rouse it up, and exercise it in this noble study; but in an ordinary soul it must be by intervals and with moderation; it will otherwise grow besotted if continually intent upon it. I found it necessary, when I was young, to put myself in mind and solicit myself to keep me to my duty; gaiety and health do not, they say, so well agree with those grave and serious meditations: I am at present in another state: the conditions of age but too much put me in mind, urge me to wisdom, and preach to me. From the excess of sprightliness I am fallen into that of severity,

which is much more troublesome; and for that reason I now and then suffer myself purposely a little to run into disorder, and occupy my mind in wanton and youthful thoughts, wherewith it diverts itself. I am of late but too reserved, too heavy, and too ripe; years every day read to me lectures of coldness and temperance. This body of mine avoids disorder and dreads it; ’tis now my body’s turn to guide my mind towards reformation; it governs, in turn, and more rudely and imperiously than the other; it lets me not an hour alone, sleeping or waking, but is always preaching to me death, patience, and repentance. I now defend myself from temperance, as I have formerly done from pleasure; it draws me too much back, and even to stupidity. Now I will be master of myself, to all intents and purposes; wisdom has its excesses, and has no less need of moderation than folly. Therefore, lest I should wither, dry up, and overcharge myself with prudence, in the intervals and truces my infirmities allow me:—“That my mind may not eternally be intent upon my ills,”

I gently turn aside, and avert my eyes from the stormy and cloudy sky I have before me, which, thanks be to God, I regard without fear, but not without meditation and study, and amuse myself in the remembrance of my better years:—

“The mind wishes to have what it has lost, and throws itself wholly into memories of the past.”

Let childhood look forward and age backward; was not this the signification of Janus’ double face? Let years draw me along if they will, but it shall be backward; as long as my eyes can discern the pleasant season expired, I shall now and then turn them that way; though it escape from my blood and veins, I shall not, however, root the image of it out of my memory:—

“ ’Tis to live twice to be able to enjoy one’s former life again.”

Plato ordains that old men should be present at the exercises, dances, and sports of young people, that they may rejoice in others for the activity and beauty of body

which is no more in themselves, and call to mind the grace and comeliness of that flourishing age; and wills that in these recreations the honor of the prize should be given to that young man who has most diverted the company. I was formerly wont to mark cloudy and gloomy days as extraordinary; these are now my ordinary days; the extraordinary are the clear and bright; I am ready to leap for joy, as for an unwonted favor, when nothing happens me. Let me tickle myself, I cannot force a poor smile from this wretched body of mine; I am only merry in conceit and in dreaming, by artifice to divert the melancholy of age; but, in faith, it requires another remedy than a dream. A weak contest of art against nature. ’Tis great folly to lengthen and anticipate human incommodities, as every one does; I had rather be a less while old than be old before I am really so. I seize on even the least occasions of pleasure I can meet. I know very well, by hearsay, several sorts of prudent pleasures, effectually so, and glorious to boot; but opinion has not power enough over me to give me an appetite to them. I covet not so much to have them magnanimous, magnificent, and pompous, as I do to have them sweet, facile, and ready:—“We depart from nature and give ourselves to the people, who understand nothing.”

My philosophy is in action, in natural and present practice, very little in fancy: what if I should take pleasure in playing at noisettes (Odd or even?) or at top?—

“He did not sacrifice his health even to rumors.”

Pleasure is a quality of very little ambition; it thinks itself rich enough of itself without any addition of repute; and is best pleased where most retired. A young man should be whipped who pretends to a taste in wine and sauces; there was nothing which, at that age, I less valued or knew: now I begin to learn; I am very much ashamed on’t; but what should I do? I am more ashamed and vexed at the occasions that put me upon’t. ’Tis for us to dote and trifle away the time, and for young men to stand upon their reputation and nice punctilios; they are

going towards the world and the world’s opinion; we are retiring from it:—“Let them reserve to themselves arms, horses, spears, clubs, tennis, swimming, and races; and of many sports leave to us old men cards and dice;”

the laws themselves send us home. I can do no less in favor of this wretched condition into which my age has thrown me than furnish it with toys to play withal, as they do children; and, in truth, we become such. Both wisdom and folly will have enough to do to support and relieve me by alternate services in this calamity of age:—

“Mingle with counsels a brief interval of folly.”

I accordingly avoid the lightest punctures; and those that formerly would not have rippled the skin, now pierce me through and through: my habit of body is now so naturally declining to ill:—

“In a fragile body every shock is obnoxious:”

“And the infirm mind can bear no difficult exertion.”

I have ever been very susceptibly tender as to offences: I am much more tender now, and open throughout.

“And little force suffices to break what was cracked before.”

My judgment restrains me from kicking against and murmuring at the inconveniences that nature orders me to endure, but it does not take away my feeling them: I, who have no other thing in my aim but to live and be merry, would run from one end of the world to the other to seek out one good year of pleasant and jocund tranquillity. A melancholic and dull tranquillity may be enough for me, but it benumbs and stupefies me; I am not contented with it. If there be any person, any knot of good company in country or city, in France or elsewhere, resident or in motion, who can like my humor, and whose humors I can like, let them but whistle and I will run and furnish them with essays in flesh and bone.

Seeing it is the privilege of the mind to rescue itself from old age, I advise mine to it with all the power I have; let it meanwhile continue green, and flourish if it can, like mistletoe upon a dead tree. But I fear ’tis a traitor; it has contracted so strict a fraternity with the body that it leaves me at every turn, to follow that in its need. I wheedle and deal with it apart in vain; I try in vain to wean it from this correspondence, to no effect quote to it Seneca and Catullus, and ladies and royal masques; if its companion have the stone, it seems to have it too; even the faculties that are most peculiarly and properly its own cannot then perform their functions, but manifestly appear stupefied and asleep; there is no sprightliness in its productions, if there be not at the same time an equal proportion in the body too.

Our masters are to blame, that in searching out the causes of the extraordinary emotions of the soul, besides attributing it to a divine ecstasy, love, martial fierceness, poesy, wine, they have not also attributed a part to health: a boiling, vigorous, full, and lazy health, such as formerly the verdure of youth

and security, by fits, supplied me withal; that fire of sprightliness and gaiety darts into the mind flashes that are lively and bright beyond our natural light, and of all enthusiasms the most jovial, if not the most extravagant.It is, then, no wonder if a contrary state stupefy and clog my spirit, and produce a contrary effect:—

“It rises to no effort; it languishes with the body;”

and yet would have me obliged to it for giving, as it wants to make out, much less consent to this stupidity than is the ordinary case with men of my age. Let us, at least, whilst we have truce, drive away incommodities and difficulties from our commerce:—

“Whilst we can, let us banish old age from the brow.”

“Sour things are to be sweetened with those that are pleasant.”

I love a gay and civil wisdom, and fly from all sourness and austerity of manners, all repellent mien being suspected by me:—

“The arrogant sadness of a crabbed face.”

“And the dull crowd also has its voluptuaries.”

I am very much of Plato’s opinion, who says that facile or harsh humors are great indications of the good or ill disposition of the mind. Socrates had a constant countenance, but serene and smiling, not sourly austere, like the elder Crassus, whom no one ever saw laugh. Virtue is a pleasant and gay quality.

I know very well that few will quarrel with the license of my writings, who have not more to quarrel with in the license of their own thoughts: I conform myself well enough to their inclinations, but I offend their eyes. ’Tis a fine humor to strain the writings of Plato, to wrest his pretended intercourses with Phaedo, Dion, Stella, and Archeanassa:—

“Let us not be ashamed to speak what we are not ashamed to think.”

I hate a froward and dismal spirit, that slips over all the pleasures of life and seizes and

feeds upon misfortunes; like flies, that cannot stick to a smooth and polished body, but fix and repose themselves upon craggy and rough places, and like cupping-glasses, that only suck and attract bad blood.As to the rest, I have enjoined myself to dare to say all that I dare to do; even thoughts that are not to be published, displease me; the worst of my actions and qualities do not appear to me so evil as I find it evil and base not to dare to own them. Every one is wary and discreet in confession, but men ought to be so in action; the boldness of doing ill is in some sort compensated and restrained by the boldness of confessing it. Whoever will oblige himself to tell all, should oblige himself to do nothing that he must be forced to conceal. I wish that this excessive license of mine may draw men to freedom, above these timorous and mincing virtues sprung from our imperfections, and that at the expense of my immoderation I may reduce them to reason. A man must see and study his vice to correct it; they who conceal it from others, commonly conceal it from themselves; and do not think it close

enough, if they themselves see it: they withdraw and disguise it from their own consciences:—“Why does no man confess his vices? because he is yet in them; ’tis for a waking man to tell his dream.”

The diseases of the body explain themselves by their increase; we find that to be the gout which we called a rheum or a strain; the diseases of the soul, the greater they are, keep themselves the most obscure; the most sick are the least sensible; therefore it is that with an unrelenting hand they must often, in full day, be taken to task, opened, and torn from the hollow of the heart. As in doing well, so in doing ill, the mere confession is sometimes satisfaction. Is there any deformity in doing amiss, that can excuse us from confessing ourselves? It is so great a pain to me to dissemble, that I evade the trust of another’s secrets, wanting the courage to disavow my knowledge. I can keep silent, but deny I cannot without the greatest trouble and violence to myself imaginable: to be very secret, a man must be so by nature,

not by obligation. ’Tis little worth, in the service of a prince, to be secret, if a man be not a liar to boot. If he who asked Thales the Milesian whether he ought solemnly to deny that he had committed adultery, had applied himself to me, I should have told him that he ought not to do it; for I look upon lying as a worse fault than the other. Thales advised him quite contrary, bidding him swear to shield the greater fault by the less: nevertheless, this counsel was not so much an election as a multiplication of vice. Upon which let us say this in passing, that we deal liberally with a man of conscience when we propose to him some difficulty in counterpoise of vice; but when we shut him up betwixt two vices, he is put to a hard choice: as Origen was either to idolatrize or to suffer himself to be carnally abused by a great Ethiopian slave they brought to him. He submitted to the first condition, and wrongly, people say. Yet those women of our times are not much out, according to their error, who protest they had rather burden their consciences with ten men than one mass.If it be indiscretion so to publish one’s

errors, yet there is no great danger that it pass into example and custom; for Ariston said, that the winds men most fear are those that lay them open. We must tuck up this ridiculous rag that hides our manners: they send their consciences to the stews, and keep a starched countenance: even traitors and assassins espouse the laws of ceremony, and there fix their duty. So that neither can injustice complain of incivility, nor malice of indiscretion. ’Tis pity but a bad man should be a fool to boot, and that outward decency should palliate his vice: this rough-cast only appertains to a good and sound wall, that deserves to be preserved and whited.In favor of the Huguenots, who condemn our auricular and private confession, I confess myself in public, religiously and purely: St. Augustin, Origen, and Hippocrates have published the errors of their opinions; I, moreover, of my manners. I am greedy of making myself known, and I care not to how many, provided it be truly; or to say better, I hunger for nothing; but I mortally hate to be mistaken by those who happen to learn my name. He who does all things for honor and

glory, what can he think to gain by showing himself to the world in a vizor, and by concealing his true being from the people? Praise a humpback for his stature, he has reason to take it for an affront: if you are a coward, and men commend you for your valor, is it of you they speak? They take you for another. I should like him as well who glorifies himself in the compliments and congees that are made him as if he were master of the company, when he is one of the least of the train. Archelaus, king of Macedon, walking along the street, somebody threw water on his head, which they who were with him said he ought to punish: “Aye, but,” said he, “whoever it was, he did not throw the water upon me, but upon him whom he took me to be.” Socrates being told that people spoke ill of him, “Not at all,” said he, “there is nothing in me of what they say.” For my part, if any one should recommend me as a good pilot, as being very modest or very chaste, I should owe him no thanks; and so, whoever should call me traitor, robber, or drunkard, I should be as little concerned. They who do not rightly know themselves, may feed themselves with false approbations; not I, who see myself, and who examine myself even to my very bowels, and who very well know what is my due. I am content to be less commended, provided I am better known. I may be reputed a wise man in such a sort of wisdom as I take to be folly. I am vexed that my Essays only serve the ladies for a common piece of furniture, and a piece for the hall; this chapter will make me part of the water-closet. I love to traffic with them a little in private; public conversation is without favor and without savor. In farewells, we oftener than not heat our affections towards the things we take leave of; I take my last leave of the pleasures of this world: these are our last embraces.But let us come to my subject: what has the act of generation, so natural, so necessary, and so just, done to men, to be a thing not to be spoken of without blushing, and to be excluded from all serious and moderate discourse? We boldly pronounce kill, rob, betray, and that we dare only to do betwixt the teeth. Is it to say, the less we expend in words, we may pay so much the more in

thinking? For it is certain that the words least in use, most seldom written, and best kept in, are the best and most generally known: no age, no manners, are ignorant of them, no more than the word bread: they imprint themselves in every one without being expressed, without voice, and without figure; and the sex that most practises it is bound to say least of it. ’Tis an act that we have placed in the franchise of silence, from which to take it is a crime even to accuse and judge it; neither dare we reprehend it but by periphrasis and picture. A great favor to a criminal to be so execrable that justice thinks it unjust to touch and see him; free, and safe by the benefit of the severity of his condemnation. Is it not here as in matter of books, that sell better and become more public for being suppressed? For my part, I will take Aristotle at his word, who says, that “bashfulness is an ornament to youth, but a reproach to old age.” These verses are preached in the ancient school, a school that I much more adhere to than the modern: its virtues appear to me to be greater, and the vices less:—“They err as much who too much forbear Venus, as they who are too frequent in her rites.”

“Goddess, still thou alone governest nature, nor without thee anything comes into light; nothing is pleasant, nothing joyful.”

I know not who could set Pallas and the Muses at variance with Venus, and make them cold towards Love; but I see no deities so well met, or that are more indebted to one another. Who will deprive the Muses of amorous imaginations, will rob them of the best entertainment they have, and of the noblest matter of their work: and who will make Love lose the communication and service of poesy, will disarm him of his best weapons: by this means they charge the god of familiarity and good will, and the protecting goddess of humanity and justice, with the vice of ingratitude and unthankfulness. I have not been so long cashiered from the state and service of this god, that my memory is not still perfect in his force and value:—

“I recognize vestiges of my old flame;”

There are yet some remains of heat and emotion after the fever:—

“Nor let this heat of youth fail me in my winter years.”

Withered and drooping as I am, I feel yet some remains of that past ardor:—

“As Aegean seas, when storms be calmed again,

That rolled their tumbling waves with troublous blast,

Do yet of tempests passed some show retain,

And here and there their swelling billows cast:”

but from what I understand of it, the force and power of this god are more lively and animated in the picture of poesy than in their own essence:—

“Verse has fingers:”

it has I know not what kind of air, more amorous than love itself. Venus is not so beautiful, naked, alive, and panting, as she is here in Virgil:—

“The goddess spoke, and throwing round

him her snowy arms in soft embraces, caresses him hesitating. Suddenly he caught the wonted flame, and the well-known warmth pierced his marrow, and ran thrilling through his shaken bones: just as when at times, with thunder, a stream of fire in lightning flashes shoots across the skies. . . . Having spoken these words, he gave her the wished embrace, and in the bosom of his spouse sought placid sleep.”All that I find fault with in considering it is, that he has represented her a little too passionate for a married Venus; in this discreet kind of coupling, the appetite is not usually so wanton, but more grave and dull. Love hates that people should hold of any but itself, and goes but faintly to work in familiarities derived from any other title, as marriage is: alliance, dowry, therein sway by reason, as much or more than grace and beauty. Men do not marry for themselves, let them say what they will; they marry as much or more for their posterity and family; the custom and interest of marriage concern our race much more than us; and therefore it is, that I like to have a match carried on by

a third hand rather than a man’s own, and by another man’s liking than that of the party himself; and how much is all this opposite to the conventions of love? And also it is a kind of incest to employ in this venerable and sacred alliance the heat and extravagance of amorous license, as I think I have said elsewhere. A man, says Aristotle, must approach his wife with prudence and temperance, lest in dealing too lasciviously with her, the extreme pleasure make her exceed the bounds of reason. What he says upon the account of conscience, the physicians say upon the account of health: “that a pleasure excessively lascivious, voluptuous, and frequent, makes the seed too hot, and hinders conception:” ’tis said, elsewhere, that to a languishing intercourse, as this naturally is, to supply it with a due and fruitful heat, a man must do it but seldom and at appreciable intervals:—“But let him thirstily snatch the joys of love and enclose them in his bosom.”

I see no marriages where the conjugal compatibility sooner fails than those that we contract

upon the account of beauty and amorous desires; there should be more solid and constant foundation, and they should proceed with greater circumspection; this furious ardor is worth nothing.They who think they honor marriage by joining love to it, do, methinks, like those who, to favor virtue, hold that nobility is nothing else but virtue. They are indeed things that have some relation to one another, but there is a great deal of difference; we should not so mix their names and titles; ’tis a wrong to them both so to confound them. Nobility is a brave quality, and with good reason introduced; but forasmuch as ’tis a quality depending upon others, and may happen in a vicious person, in himself nothing, ’tis in estimate infinitely below virtue: ’tis a virtue, if it be one, that is artificial and apparent, depending upon time and fortune: various in form, according to the country; living and mortal; without birth, as the river Nile; genealogical and common; of succession and similitude; drawn by consequence, and a very weak one. Knowledge, strength, goodness, beauty, riches, and all

other qualities, fall into communication and commerce, but this is consummated in itself, and of no use to the service of others. There was proposed to one of our kings the choice of two candidates for the same command, of whom one was a gentleman, the other not; he ordered that, without respect to quality, they should choose him who had the most merit; but where the worth of the competitors should appear to be entirely equal, they should have respect to birth: this was justly to give it its rank. A young man unknown, coming to Antigonus to make suit for his father’s command, a valiant man lately dead: “Friend,” said he, “in such preferments as these, I have not so much regard to the nobility of my soldiers as to their prowess.” And, indeed, it ought not to go as it did with the officers of the kings of Sparta, trumpeters, fiddlers, cooks, the children of whom always succeeded to their places, how ignorant soever, and were preferred before the most experienced in the trade. They of Calicut make of nobles a sort of superhuman persons: they are interdicted marriage and all but warlike employments: they may have of concubines their fill, and the women as many lovers, without being jealous of one another; but ’tis a capital and irremissible crime to couple with a person of meaner condition than themselves; and they think themselves polluted, if they have but touched one in walking along; and supposing their nobility to be marvellously interested and injured in it, kill such as only approach a little too near them: insomuch that the ignoble are obliged to cry out as they walk, like the gondoliers of Venice, at the turnings of streets for fear of jostling; and the nobles command them to step aside to what part they please: by that means these avoid what they repute a perpetual ignominy, those certain death. No time, no favor of the prince, no office, or virtue, or riches, can ever prevail to make a plebeian become noble: to which this custom contributes, that marriages are interdicted betwixt different trades; the daughter of one of the cordwainers’ guild is not permitted to marry a carpenter; and parents are obliged to train up their children precisely in their own callings, and not put them to any other trade; by which means the distinction and continuance of their fortunes are maintained.A good marriage, if there be any such, rejects the company and conditions of love, and tries to represent those of friendship. ’Tis a sweet society of life, full of constancy, trust, and an infinite number of useful and solid services and mutual obligations; which any woman who has a right taste:—

“Whom the marriage torch has joined with the desired light—”

would be loth to serve her husband in quality of a mistress. If she be lodged in his affection as a wife, she is more honorably and securely placed. When he purports to be in love with another, and works all he can to obtain his desire, let any one but ask him, on which he had rather a disgrace should fall, his wife or his mistress, which of their misfortunes would most afflict him, and to which of them he wishes the most grandeur, the answer to these questions is out of dispute in a sound marriage.

And that so few are observed to be happy, is a token of its price and value. If well formed and rightly taken, ’tis the best of all human societies: we cannot live without it, and yet we do nothing but decry it. It happens,

as with cages, the birds without despair to get in, and those within despair of getting out. Socrates being asked, whether it was more commodious to take a wife or not, “Let a man take which course he will,” said he; “he will repent.” ’Tis a contract to which the common saying:—“Man to man is either a god or a wolf,”

may very fitly be applied; there must be a concurrence of many qualities in the construction. It is found nowadays more convenient for simple and plebeian souls, where delights, curiosity, and idleness does not so much disturb it; but extravagant humors, such as mine, that hate all sorts of obligation and restraint, are not so proper for it:—

“And it is sweet to me to live with a loosened neck.”

Might I have had my own will, I would not have married Wisdom herself, if she would have had me. But ’tis to much purpose to evade it; the common custom and usance of

life will have it so. The most of my actions are guided by example, not by choice, and yet I did not go to it of my own voluntary motion; I was led and drawn to it by extrinsic occasions; for not only things that are incommodious in themselves, but also things however ugly, vicious, and to be avoided, may be rendered acceptable by some condition or accident; so unsteady and vain is all human resolution! and I was persuaded to it, when worse prepared and less tractable than I am at present, that I have tried what it is: and as great a libertine as I am taken to be, I have in truth more strictly observed the laws of marriage, than I either promised or expected. ’Tis in vain to kick, when a man has once put on his fetters: a man must prudently manage his liberty; but having once submitted to obligation, he must confine himself within the laws of common duty, at least, do what he can towards it. They who engage in this contract, with a design to carry themselves in it with hatred and contempt, do an unjust and inconvenient thing; and the fine rule that I hear pass from hand to hand amongst the women, as a sacred oracle:—“Serve thy husband as thy master, but guard thyself against him as from a traitor,”

which is to say, comport thyself towards him with a dissembled, inimical, and distrustful reverence (a cry of war and defiance), is equally injurious and hard. I am too mild for such rugged designs: to say the truth, I am not arrived to that perfection of ability and refinement of wit, to confound reason with injustice, and to laugh at all rule and order that does not please my palate; because I hate superstition, I do not presently run into the contrary extreme of irreligion. If a man does not always perform his duty, he ought at least to love and acknowledge it; ’tis treachery to marry without espousing.

Let us proceed.

Our poet represents a marriage happy in a good accord wherein nevertheless there is not much loyalty. Does he mean, that it is not impossible but a woman may give the reins to her own passion, and yield to the importunities of love, and yet reserve some duty

toward marriage, and that it may be hurt, without being totally broken? A serving man may cheat his master, whom nevertheless he does not hate. Beauty, opportunity, and destiny (for destiny has also a hand in’t):—“There is a fatality about the hidden parts: let nature have endowed you however liberally, ’tis of no use, if your good star fails you in the nick of time;”

have attached her to a stranger; though not so wholly, peradventure, but that she may have some remains of kindness for her husband. They are two designs, that have several paths leading to them, without being confounded with one another; a woman may yield to a man she would by no means have married, not only for the condition of his fortune, but for those also of his person. Few men have made a wife of a mistress, who have not repented it. And even in the other world, what an unhappy life does Jupiter lead with his, whom he had first enjoyed as a mistress? ’Tis, as the proverb runs, to befoul a basket and then put it upon one’s head. I have in

my time, in a good family, seen love shamefully and dishonestly cured by marriage: the considerations are widely different. We love at once, without any tie, two things contrary in themselves.Socrates was wont to say, that the city of Athens pleased, as ladies do whom men court for love; every one loved to come thither to take a turn, and pass away his time; but no one liked it so well as to espouse it, that is, to inhabit there, and to make it his constant residence. I have been vexed to see husbands hate their wives only because they themselves do them wrong; we should not, at all events, methinks, love them the less for our own faults; they should at least, upon the account of repentance and compassion, be dearer to us.

They are different ends, he says, and yet in some sort compatible; marriage has utility, justice, honor, and constancy for its share; a flat, but more universal pleasure: love founds itself wholly upon pleasure, and, indeed, has it more full, lively, and sharp; a pleasure inflamed by difficulty; there must be in it sting and smart: ’tis no longer love,

if without darts and fire. The bounty of ladies is too profuse in marriage, and dulls the point of affection and desire: to evade which inconvenience, do but observe what pains Lycurgus and Plato take in their laws.Women are not to blame at all, when they refuse the rules of life that are introduced into the world, forasmuch as the men made them without their help. There is naturally contention and brawling betwixt them and us; and the strictest friendship we have with them is yet mixed with tumult and tempest. In the opinion of our author, we deal inconsiderately with them in this: after we have discovered that they are, without comparison, more able and ardent in the practice of love than we, and that the old priest testified as much, who had been one while a man, and then a woman:—

“Both aspects of love were known to him:”

and moreover, that we have learned from their own mouths the proof that, in several ages, was made by an Emperor and Empress of Rome, both famous for ability in that affair! for he in one night deflowered ten

Sarmatian virgins who were his captives: but she had five-and-twenty bouts in one night, changing her man according to her need and liking:—“Ardent still, she retired, fatigued, but not satisfied:”

and that upon the dispute which happened in Cataluna, wherein a wife complaining of her husband’s too frequent addresses to her, not so much, as I conceive, that she was incommodated by it (for I believe no miracles out of religion) as under this pretence, to curtail and curb in this, which is the fundamental act of marriage, the authority of husbands over their wives, and to show that their frowardness and malignity go beyond the nuptial bed, and spurn under foot even the graces and sweets of Venus; the husband, a man truly brutish and unnatural, replied, that even on fasting days he could not subsist with less than ten courses: whereupon came out that notable sentence of the Queen of Arragon, by which, after mature deliberation of her council, this good queen, to give a rule and example to all succeeding ages of the

moderation required in a just marriage, set down six times a day as a legitimate and necessary stint; surrendering and quitting a great deal of the needs and desires of her sex, that she might, she said, establish an easy, and consequently, a permanent and immutable rule. Thereupon the doctors cry out: what must the female appetite and concupiscence be, when their reason, their reformation and virtue, are taxed at such a rate, considering the divers judgments of our appetites? for Solon, master of the law school, taxes us but at three a month, that men may not fail in point of conjugal frequentation: after having, I say, believed and preached all this, we go and enjoin them continency for their particular share, and upon the last and extreme penalties.There is no passion so hard to contend with as this, which we would have them only resist, not simply as an ordinary vice, but as an execrable abomination, worse than irreligion and parricide; whilst we, at the same time, go to’t without offence or reproach. Even those amongst us who have tried the experiment have sufficiently confessed what difficulty,

or rather impossibility, they have found by material remedies to subdue, weaken, and cool the body. We, on the contrary, would have them at once sound, vigorous, plump, high-fed, and chaste; that is to say, both hot and cold; for the marriage, which we tell them is to keep them from burning, is but small refreshment to them, as we order the matter. If they take one whose vigorous age is yet boiling, he will be proud to make it known elsewhere:—“Let there be some shame, or we shall go to law: your vigor, bought by your wife with many thousands, is no longer yours: thou hast sold it;”

Polemon the philosopher was justly by his wife brought before the judge for sowing in a barren field the seed that was due to one that was fruitful: if, on the other hand, they take a decayed fellow, they are in a worse condition in marriage than either maids or widows. We think them well provided for, because they have a man to lie with, as the Romans concluded Clodia Laeta, a vestal nun, violated, because Caligula had approached

her, though it was declared he did no more but approach her: but, on the contrary, we by that increase their necessity, forasmuch as the touch and company of any man whatever rouses their desires, that in solitude would be more quiet. And to the end, ’tis likely, that they might render their chastity more meritorious by this circumstance and consideration, Boleslas and Kinge his wife, kings of Poland, vowed it by mutual consent, being in bed together, on their very wedding day, and kept their vow in spite of all matrimonial conveniences.We train them up from their infancy to the traffic of love; their grace, dressing, knowledge, language, and whole instruction tend that way: their governesses imprint nothing in them but the idea of love, if for nothing else but by continually representing it to them, to give them a distaste for it. My daughter, the only child I have, is now of an age that forward young women are allowed to be married at; she is of a slow, thin, and tender complexion, and has accordingly been brought up by her mother after a retired and particular manner, so that she but now begins

to be weaned from her childish simplicity. She was reading before me in a French book where the word fouteau, the name of a tree very well known, occurred; the woman, to whose conduct she is committed, stopped her short a little roughly, and made her skip over that dangerous step. I let her alone, not to trouble their rules, for I never concern myself in that sort of government; feminine polity has a mysterious procedure; we must leave it to them; but if I am not mistaken the commerce of twenty lacquies could not, in six months’ time, have so imprinted in her memory the meaning, usage, and all the consequence of the sound of these wicked syllables, as this good old woman did by reprimand and interdiction:—“The maid ripe for marriage delights to learn Ionic dances, and to imitate those lascivious movements. Nay, already from her infancy she meditates criminal amours.”

Let them but give themselves the rein a little, let them but enter into liberty of discourse, we are but children to them in this science. Hear them but describe our pursuits

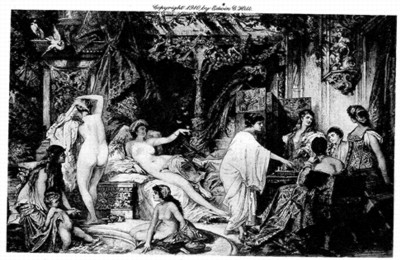

and conversation, they will very well make you understand that we bring them nothing they have not known before, and digested without our help. Is it, perhaps, as Plato says, that they have formerly been debauched young fellows? I happened one day to be in a place where I could hear some of their talk without suspicion; I am sorry I cannot repeat it. By’rlady, said I, we had need go study the phrases of Amadis, and the tales of Boccaccio and Aretin, to be able to discourse with them: we employ our time to much purpose indeed. There is neither word, example, nor step they are not more perfect in than our books; ’tis a discipline that springs with their blood:— Wooing. From painting by F. Andreotti.“Venus herself made them what they are,”

which these good instructors, nature, youth, and health, are continually inspiring them with; they need not learn, they breed it:—

“No milk-white dove, or if there be a thing more lascivious, takes so much delight in kissing as woman, wishful for every man she sees.”

So that if the natural violence of their desire were not a little restrained by fear and honor, which were wisely contrived for them, we should be all shamed. All the motions in the world resolve into and tend to this conjunction; ’tis a matter infused throughout: ’tis a centre to which all things are directed. We yet see the edicts of the old and wise Rome made for the service of love, and the precepts of Socrates for the instruction of courtezans:—

“Quid? quod libelli Stoici inter sericos Jacere pulvillos amant;”

Zeno, amongst his laws, also regulated the motions to be observed in getting a maidenhead. What was the philosopher Strato’s book Of Carnal Conjunction? And what did Theophrastus treat of in those he intituled, the one The Lover, and the other Of Love? Of what Aristippus in his Of Former Delights? What do the so long and lively descriptions in Plato of the loves of his time pretend to? and the book called the Lover, of Demetrius Phalereus? and Clinias, or the

Ravished Lover, of Heraclides; and that of Antisthenes, Of Getting Children, or, Of Weddings, and the other, Of the Master or the Lover? And that of Aristo: Of Amorous Exercises? What those of Cleanthes: one, Of Love, the other, Of the Art of Loving? The amorous dialogues of Sphaereus? and the fable of Jupiter and Juno, of Chrysippus, impudent beyond all toleration? And his fifty so lascivious epistles? I will let alone the writings of the philosophers of the Epicurean sect, protectress of voluptuousness. Fifty deities were, in time past, assigned to this office; and there have been nations where, to assuage the lust of those who came to their devotion, they kept men and women in their temples for the worshippers to lie with; and it was an act of ceremony to do this before they went to prayers:—“Forsooth incontinency is necessary for continency’s sake; a conflagration is extinguished by fire.”

In the greatest part of the world, that member of our body was deified; in the same

province, some flayed off the skin to offer and consecrate a piece; others offered and consecrated their seed. In another, the young men publicly cut through betwixt the skin and the flesh of that part in several places, and thrust pieces of wood into the openings as long and thick as they would receive, and of these pieces of wood afterwards made a fire as an offering to their gods; and were reputed neither vigorous nor chaste, if by the force of that cruel pain they seemed to be at all dismayed. Elsewhere the most sacred magistrate was reverenced and acknowledged by that member: and in several ceremonies the effigy of it was carried in pomp to the honor of various divinities. The Egyptian ladies, in their Bacchanalia, each carried one finely carved of wood about their necks, as large and heavy as she could so carry it; besides which, the statue of their god presented one, which in greatness surpassed all the rest of his body. The married women, near the place where I live, make of their kerchiefs the figure of one upon their foreheads, to glorify themselves in the enjoyment they have of it; and coming to be widows, they throw it behind, and cover it with their headcloths. The most modest matrons of Rome thought it an honor to offer flowers and garlands to the god Priapus; and they made the virgins, at the time of their espousals, sit upon his shameful parts. And I know not whether I have not in my time seen some air of like devotion. What was the meaning of that ridiculous piece of the chaussure of our forefathers, and that is still worn by our Swiss? To what end do we make a show of our implements in figure under our breeches, and often, which is worse, above their natural size, by falsehood and imposture? I have half a mind to believe that this sort of vestment was invented in the better and more conscientious ages, that the world might not be deceived, and that every one should give a public account of his proportions: the simple nations wear them yet, and near about the real size. In those days, the tailor took measure of it, as the shoemaker does now of a man’s foot. That good man, who, when I was young, gelded so many noble and ancient statues in his great city, that they might not corrupt the sight of the ladies, according to the advice of this other ancient worthy:—“ ’Tis the beginning of wickedness to expose their persons among the citizens,”

should have called to mind, that, as in the mysteries of the Bona Dea, all masculine appearance was excluded, he did nothing, if he did not geld horses and asses—in short, all nature:—

“So that all living things, men and animals, wild or tame, and fish and gaudy fowl, rush to this flame of love.”

The gods, says Plato, have given us one disobedient and unruly member that, like a furious animal, attempts, by the violence of its appetite, to subject all things to it; and so they have given to women one like a greedy and ravenous animal, which, if it be refused food in season, grows wild, impatient of delay, and infusing its rage into their bodies, stops the passages, and hinders respiration, causing a thousand ills, till, having imbibed the fruit of the common thirst,

it has plentifully bedewed the bottom of their matrix. Now my legislator should also have considered that, peradventure, it were a chaster and more fruitful usage to let them know the fact as it is betimes, than permit them to guess according to the liberty and heat of their own fancy; instead of the real parts they substitute, through hope and desire, others that are three times more extravagant; and a certain friend of mine lost himself by producing his in place and time when the opportunity was not present to put them to their more serious use. What mischief do not those pictures of prodigious dimension do that the boys make upon the staircases and galleries of the royal houses? they give the ladies a cruel contempt of our natural furniture. And what do we know but that Plato, after other well-instituted republics, ordered that the men and women, old and young, should expose themselves naked to the view of one another, in his gymnastic exercises, upon that very account? The Indian women who see the men in their natural state, have at least cooled the sense of seeing. And let the women of the kingdom of Pegu say what they will, who below the waist have nothing to cover them but a cloth slit before, and so strait, that what decency and modesty soever they pretend by it, at every step all is to be seen, that it is an invention to allure the men to them, and to divert them from boys, to whom that nation is generally inclined; yet, peradventure they lose more by it than they get, and one may venture to say, that an entire appetite is more sharp than one already half-glutted by the eyes. Livia was wont to say, that to a virtuous woman a naked man was but a statue. The Lacedaemonian women, more virgins when wives than our daughters are, saw every day the young men of their city stripped naked in their exercises, themselves little heeding to cover their thighs in walking, believing themselves, says Plato, sufficently covered by their virtue without any other robe. But those, of whom St. Augustin speaks, have given nudity a wonderful power of temptation, who have made it a doubt, whether women at the day of judgment shall rise again in their own sex, and not rather in ours, for fear of tempting us again in that holy state. In brief, we allure and flesh them by all sorts of ways: we incessantly heat and stir up their imagination, and then we find fault. Let us confess the truth; there is scarce one of us who does not more apprehend the shame that accrues to him by the vices of his wife than by his own, and that is not more solicitous (a wonderful charity) of the conscience of his virtuous wife than of his own; who had not rather commit theft and sacrilege, and that his wife was a murderess and a heretic, than that she should not be more chaste than her husband: an unjust estimate of vices. Both we and they are capable of a thousand corruptions more prejudicial and unnatural than lust: but we weigh vices, not according to nature, but according to our interest; by which means they take so many unequal forms.The austerity of our decrees renders the application of women to this vice more violent and vicious than its own condition needs, and engages it in consequences worse than their cause: they will readily offer to go to the law courts to seek for gain, and to the wars to get reputation, rather than in the

midst of ease and delights, to have to keep so difficult a guard. Do not they very well see that there is neither merchant nor soldier who will not leave his business to run after this sport, or the porter or cobbler, toiled and tired out as they are with labor and hunger?—“Wouldst thou not exchange all that the wealthy Achaemenes had, or the Mygdonian riches of fertile Phrygia, for one ringlet of Licymnia’s hair? or the treasures of the Arabians, when she turns her head to you for fragrant kisses, or with easily assuaged anger denies them, which she would rather by far you took by force, and sometimes herself snatches one?”

I do not know whether the exploits of Alexander and Caesar really surpass the resolution of a beautiful young woman, bred up after our fashion, in the light and commerce of the world, assailed by so many contrary examples, and yet keeping herself entire in the midst of a thousand continual and powerful solicitations. There is no doing more difficult than that not doing, nor more active: I hold it more easy to carry a suit of armor

all the days of one’s life than a maidenhead; and the vow of virginity of all others is the most noble, as being the hardest to keep:—“Diaboli virtus in lumbis est,”

says St. Jerome. We have, doubtless, resigned to the ladies the most difficult and most vigorous of all human endeavors, and let us resign to them the glory too. This ought to encourage them to be obstinate in it; ’tis a brave thing for them to defy us, and to spurn under foot that vain preeminence of valor them; they will find if they do but observe it, that they will not only be much more esteemed for it, but also much more beloved. A gallant man does not give over his pursuit for being refused, provided it be a refusal of chastity, and not of choice; we may swear, threaten, and complain to much purpose; we therein do but lie, for we love them all the better: there is no allurement like modesty, if it be not rude and crabbed. ’Tis stupidity and meanness to be obstinate against hatred and disdain; but against a virtuous and constant resolution,

mixed with good-will, ’tis the exercise of a noble and generous soul. They may acknowledge our service to a certain degree, and give us civilly to understand that they disdain us not; for the law that enjoins them to abominate us because we adore them, and to hate us because we love them, is certainly very cruel, if but for the difficulty of it. Why should they not give ear to our offers and requests, so long as they are kept within the bounds of modesty? wherefore should we fancy them to have other thoughts within, and to be worse than they seem? A queen of our time said with spirit, “that to refuse these courtesies is a testimony of weakness in women and a self-accusation of facility, and that a lady could not boast of her chastity who was never tempted.” The limits of honor are not cut so short; they may give themselves a little rein, and relax a little without being faulty: there lies on the frontier some space free, indifferent, and neuter. He that has beaten and pursued her into her fort is a strange fellow if he be not satisfied with his fortune: the price of the conquest is considered by the difficulty. Would you know what impression your service and merit have made in her heart? Judge of it by her behavior. Such a one may grant more, who does not grant so much. The obligation of a benefit wholly relates to the good will of those who confer it: the other coincident circumstances are dumb, dead, and casual; it costs her dearer to grant you that little, than it would do her companion to grant all. If in anything rarity give estimation, it ought especially in this: do not consider how little it is that is given, but how few have it to give; the value of money alters according to the coinage and stamp of the place. Whatever the spite and indiscretion of some may make them say in the excess of their discontent, virtue and truth will in time recover all the advantage. I have known some whose reputation has for a great while suffered under slander, who have afterwards been restored to the world’s universal approbation by their mere constancy without care or artifice; every one repents, and gives himself the lie for what he has believed and said; and from girls a little suspected they have been afterward advanced to the first rank amongst the ladies of honor. Somebody told Plato that all the world spoke ill of him. “Let them talk,” said he; “I will live so as to make them change their note.” Besides the fear of God, and the value of so rare a glory, which ought to make them look to themselves, the corruption of the age we live in compels them to it; and if I were they, there is nothing I would not rather do than intrust my reputation in so dangerous hands. In my time the pleasure of telling (a pleasure little inferior to that of doing) was not permitted but to those who had some faithful and only friend; but now the ordinary discourse and common table-talk is nothing but boasts of favors received and the secret liberality of ladies. In earnest, ’tis too abject, too much meanness of spirit, in men to suffer such ungrateful, indiscreet, and giddy-headed people so to persecute, forage, and rifle those tender and charming favors.This our immoderate and illegitimate exasperation against this vice springs from the most vain and turbulent disease that afflicts human minds, which is jealousy:—

“Who says that one light should not be lighted from another light? Let them give ever so much, as much ever remains to lose;”

she, and envy, her sister, seem to me to be the most foolish of the whole troop. As to the last, I can say little about it; ’tis a passion that, though said to be so mighty and powerful, had never to do with me. As to the other, I know it by sight, and that’s all. Beasts feel it; the shepherd Cratis, having fallen in love with a she-goat, the he-goat, out of jealousy, came, as he lay asleep, to butt the head of the female, and crushed it. We have raised this fever to a greater excess by the examples of some barbarous nations; the best disciplined have been touched with it, and ’tis reason, but not transported:—

“Never did adulterer slain by a husband stain with purple blood the Stygian waters.”

Lucullus, Caesar, Pompey, Antony, Cato, and other brave men were cuckolds, and knew it, without making any bustle about it; there was in those days but one coxcomb, Lepidus,

that died for grief that his wife had used him so:—“Wretched man! when, taken in the fact, thou wilt be dragged out of doors by the heels, and suffer the punishment of thy adultery:”

and the god of our poet, when he surprised one of his companions with his wife, satisfied himself by putting them to shame only:—

“And one of the merry gods wishes that he should himself like to be so disgraced:”

and nevertheless took anger at the lukewarm embraces she gave him, complaining that upon that account she was grown jealous of his affection:—

“Dost thou seek causes from above? Why, goddess, has your confidence in me ceased?”

lo! she entreats arms for her bastard:—

“I, a mother, ask armour for a son,”

which are freely granted; and Vulcan speaks honorably of Aeneas:—

“Arms are to be made for a valiant hero,”

with, in truth, a more than human humanity. And I am willing to leave this excess of kindness to the gods:—

“Nor is it fit to compare men with gods.”

As to the confusion of children, besides that the gravest legislators ordain and affect it in their republics, it touches not the women, where this passion is, I know not how, much better seated:—

“Often was Juno, greatest of the heaven-dwellers, enraged by her husband’s daily infidelities.”

When jealousy seizes these poor souls, weak and incapable of resistance, ’tis pity to see how miserably it torments and tyrannizes over them; it insinuates itself into them under the title of friendship, but after it has once possessed them, the same causes that served for a foundation of good-will serve them for a foundation of mortal hatred. ’Tis, of all the diseases of the mind, that which the most things serve for aliment and the fewest for

remedy: the virtue, health, merit, reputation of the husband are incendiaries of their fury and ill-will:—“No enmities are bitter, save that of love.”

This fever defaces and corrupts all they have of beautiful and good besides; and there is no action of a jealous woman, let her be how chaste and how good a housewife soever, that does not relish of anger and wrangling; ’tis a furious agitation, that rebounds them to an extremity quite contrary to its cause. This held good with one Octavius at Rome. Having lain with Pontia Posthumia, he augmented love by fruition, and solicited with all importunity to marry her: unable to persuade her, this excessive affection precipitated him to the effects of the most cruel and mortal hatred: he killed her. In like manner, the ordinary symptoms of this other amorous disease are intestine hatreds, private conspiracies, and cabals:—

“And it is known what an angry woman is capable of doing,”

and a rage which so much the more frets

itself, as it is compelled to excuse itself by a pretence of good-will.Now, the duty of chastity is of a vast extent; is it the will that we would have them restrain? This is a very supple and active thing; a thing very nimble, to be stayed. How? if dreams sometimes engage them so far that they cannot deny them: it is not in them, nor, peradventure, in chastity itself, seeing that is a female, to defend itself from lust and desire. If we are only to trust to their will, what a case are we in, then? Do but imagine what crowding there would be amongst men in pursuance of the privilege to run full speed, without tongue or eyes, into every woman’s arms who would accept them. The Scythian women put out the eyes of all their slaves and prisoners of war, that they might have their pleasure of them, and they never the wiser. O, the furious advantage of opportunity! Should any one ask me, what was the first thing to be considered in love matters, I should answer that it was how to take a fitting time; and so the second; and so the third—’tis a point that can do everything. I have sometimes wanted fortune, but

I have also sometimes been wanting to myself in matters of attempt. God help him, who yet makes light of this! There is greater temerity required in this age of ours, which our young men excuse under the name of heat; but should women examine it more strictly, they would find that it rather proceeds from contempt. I was always superstitiously afraid of giving offence, and have ever had a great respect for her I loved: besides, he who in this traffic takes away the reverence, defaces at the same time the lustre. I would in this affair have a man a little play the child, the timorous, and the servant. If not altogether in this, I have in other things some air of the foolish bashfulness whereof Plutarch makes mention; and the course of my life has been divers ways hurt and blemished with it; a quality very ill suiting my universal form: and, indeed, what are we but sedition and discrepancy? I am as much out of countenance to be denied as I am to deny; and it so much troubles me to be troublesome to others that on occasions where duty compels me to try the good-will of any one in a thing that is doubtful and that will be chargeable to him, I do it very faintly, and very much against my will: but if it be for my own particular (whatever Homer truly says, that modesty is a foolish virtue in an indigent person), I commonly commit it to a third person to blush for me, and deny those who employ me with the same difficulty: so that it has sometimes befallen me to have had a mind to deny, when I had not the power to do it.’Tis folly, then, to attempt to bridle in women a desire that is so powerful in them, and so natural to them. And when I hear them brag of having so maidenly and so temperate a will, I laugh at them: they retire too far back. If it be an old toothless trot, or a young dry consumptive thing, though it be not altogether to be believed, at least they may say it with more similitude of truth. But they who still move and breathe, talk at that ridiculous rate to their own prejudice, by reason that inconsiderate excuses are a kind of self-accusation; like a gentleman, a neighbor of mine, suspected to be insufficient:—

“Languidior tenera cui pendens sicula beta,

Numquam se mediam sustulit ad tunicam,”

who three or four days after he was married, to justify himself, went about boldly swearing that he had ridden twenty stages the night before: an oath that was afterwards made use of to convict him of his ignorance in that affair, and to divorce him from his wife. Besides, it signifies nothing, for there is neither continency nor virtue where there are no opposing desires. It is true, they may say, but we will not yield; saints themselves speak after that manner. I mean those who boast in good gravity of their coldness and insensibility, and who expect to be believed with a serious countenance; for when ’tis spoken with an affected look, when their eyes give the lie to their tongue, and when they talk in the cant of their profession, which always goes against the hair, ’tis good sport. I am a great servant of liberty and plainness; but there is no remedy; if it be not wholly simple or childish, ’tis silly, and unbecoming ladies in this commerce, and presently runs into impudence. Their disguises and figures only serve to cozen fools; lying is there in its seat of honor; ’tis a by-way, that by a back-door leads us to truth. If we cannot curb their

imagination, what would we have from them. Effects? There are enough of them that evade all foreign communication, by which chastity may be corrupted:—“He often does that which he does without a witness;”

and those which we fear the least are, peradventure, most to be feared; their sins that make the least noise are the worst:—

“I am less offended with a more absolute strumpet.”

There are ways by which they may lose their virginity without prostitution, and, which is more, without their knowledge:—

“By malevolence, or unskilfulness, or accident, the midwife, seeking with the hand to test some maiden’s virginity, has sometimes destroyed it.”

Such a one, by seeking her maidenhead, has lost it; another by playing with it has destroyed it. We cannot precisely circumscribe the actions, we interdict them; they must guess at our meaning under general and

doubtful terms; the very idea we invent for their chastity is ridiculous: for, amongst the greatest patterns that I have is Fatua, the wife of Faunus: who never, after her marriage, suffered herself to be seen by any man whatever; and the wife of Hiero, who never perceived her husband’s stinking breath, imagining that it was common to all men. They must become insensible and invisible to satisfy us.Now let us confess that the knot of this judgment of duty principally lies in the will; there have been husbands who have suffered cuckoldom, not only without reproach or taking offence at their wives, but with singular obligation to them and great commendation of their virtue. Such a woman has been, who prized her honor above her life, and yet has prostituted it to the furious lust of a mortal enemy, to save her husband’s life, and who, in so doing, did that for him she would not have done for herself! This is not the place wherein we are to multiply these examples; they are too high and rich to be set off with so poor a foil as I can give them here; let us reserve them for a nobler place; but for

examples of ordinary lustre, do we not every day see women amongst us who surrender themselves for their husbands’ sole benefit, and by their express order and mediation? and, of old, Phaulius the Argian, who offered his to King Philip out of ambition; as Galba did it out of civility, who, having entertained Maecenas at supper, and observing that his wife and he began to cast glances at one another and to make eyes and signs, let himself sink down upon his cushion, like one in a profound sleep, to give opportunity to their desires: which he handsomely confessed, for thereupon a servant having made bold to lay hands on the plate upon the table, he frankly cried, “What, you rogue? do you not see that I only sleep for Maecenas?” Such there may be, whose manners may be lewd enough, whose will may be more reformed than another, who outwardly carries herself after a more regular manner. As we see some who complain of having vowed chastity before they knew what they did; and I have also known others really complain of having been given up to debauchery before they were of the years of discretion. The vice of the parents or the impulse of nature, which is a rough counsellor, may be the cause.In the East Indies, though chastity is of singular reputation, yet custom permitted a married woman to prostitute herself to any one who presented her with an elephant, and that with glory, to have been valued at so high a rate. Phaedo the philosopher, a man of birth, after the taking of his country Elis, made it his trade to prostitute the beauty of his youth, so long as it lasted, to any one that would, for money thereby to gain his living: and Solon was the first in Greece, ’tis said, who by his laws gave liberty to women, at the expense of their chastity, to provide for the necessities of life; a custom that Herodotus says had been received in many governments before his time. And besides, what fruit is there of this painful solicitude? For what justice soever there is in this passion, we are yet to consider whether it turns to account or no: does any one think to curb them, with all his industry?—

“Put on a lock; shut them up under a guard; but who shall guard the guard? she is wary, and begins with them.”

What commodity will not serve their turn, in so knowing an age?

Curiosity is vicious throughout; but ’tis pernicious here. ’Tis folly to examine into a disease for which there is no physic that does not inflame and make it worse; of which the shame grows still greater and more public by jealousy, and of which the revenge more wounds our children than it heals us. You wither and die in the search of so obscure a proof. How miserably have they of my time arrived at that knowledge who have been so unhappy as to have found it out? If the informer does not at the same time apply a remedy and bring relief, ’tis an injurious information, and that better deserves a stab than the lie. We no less laugh at him who takes pains to prevent it, than at him who is cuckold and knows it not. The character of cuckold is indelible: who once has it carries it to his grave; the punishment proclaims it more than the fault. It is to much purpose to drag out of obscurity and doubt our private misfortunes, thence to expose them on tragic scaffolds; and misfortunes that only hurt us by being known, for we say a good

wife or a happy marriage, not that they are really so, but because no one says to the contrary. Men should be so discreet as to evade this tormenting and unprofitable knowledge: and the Romans had a custom, when returning from any expedition, to send home before to acquaint their wives with their coming, that they might not surprise them; and to this purpose it is that a certain nation has introduced a custom, that the priest shall on the wedding-day open the way to the bride, to free the husband from the doubt and curiosity of examing in the first assault, whether she comes a virgin to his bed, or damaged by a strange amour.But the world talks about it. I know a hundred honest men cuckolds, honestly and not unbeseemingly; a worthy man is pitied, not disesteemed for it. Order it so that your virtue may conquer your misfortune; that good men may curse the occasion, and that he who wrongs you may tremble but to think on’t. And, moreover, who escapes being talked of at the same rate, from the least even to the greatest?—

“Who was a man better than thee, base one, in many things.”

Seest thou how many honest men are reproached with this in thy presence; believe that thou art no more spared elsewhere. But, the very ladies will be laughing too; and what are they so apt to laugh at in this virtuous age of ours as at a peaceable and well-composed marriage? Each amongst you has made somebody cuckold; and nature runs much in parallel, in compensation, and turn for turn. The frequency of this accident ought long since to have made it more easy; ’tis now passed into custom.

Miserable passion! which has this also, that it is incommunicable:—

“Fortune also refuses ear to our complaints;”

for to what friend dare you intrust your griefs, who, if he does not laugh at them, will not make use of the occasion to get a share of the quarry? The sharps, as well as the sweets of marriage, are kept secret by

the wise; and amongst its other troublesome conditions this to a prating fellow, as I am, is one of the chief, that custom has rendered it indecent and prejudicial to communicate to any one all that a man knows and all that a man feels.To give women the same counsel against jealousy would be so much time lost; their very being is so made up of suspicion, vanity, and curiosity, that to cure them by any legitimate way is not to be hoped. They often recover of this infirmity by a form of health much more to be feared than the disease itself; for as there are enchantments that cannot take away the evil but by throwing it upon another, they also willingly transfer this ever to their husbands, when they shake it off themselves. And yet I know not, to speak truth, whether a man can suffer worse from them than their jealousy; ’tis the most dangerous of all their conditions, as the head is of all their members. Pittacus used to say, that every one had his trouble, and that his was the jealous head of his wife; but for which he should think himself perfectly happy. A mighty inconvenience, sure, which

could poison the whole life of so just, so wise, and so valiant a man; what must we other little fellows do? The senate of Marseilles had reason to grant him his request who begged leave to kill himself that he might be delivered from the clamor of his wife; for ’tis a mischief that is never removed but by removing the whole piece; and that has no remedy but flight or patience, though both of them very hard. He was, methinks, an understanding fellow who said, ’twas a happy marriage betwixt a blind wife and a deaf husband.Let us also consider whether the great and violent severity of obligation we enjoin them does not produce two effects contrary to our design: namely, whether it does not render the pursuants more eager to attack, and the women more easy to yield. For as to the first, by raising the value of the place, we raise the value and the desire of the conquest. Might it not be Venus herself, who so cunningly enhanced the price of her merchandise, by making the laws her bawds; knowing how insipid a delight it would be that was not heightened by fancy and hardness to

achieve? In short, ’tis all swine’s flesh, varied by sauces, as Flaminius’ host said. Cupid is a roguish god, who makes it his sport to contend with devotion and justice: ’tis his glory that his power mates all powers, and that all other rules give place to his:—“And seeks out a motive for his misdeed.”

As to the second point; should we not be less cuckolds, if we less feared to be so? according to the humor of women whom interdiction incites, and who are more eager, being forbidden:—

“Where thou wilt, they won’t; where thou wilt not, they spontaneously agree; they are ashamed to go in the permitted path.”

What better interpretation can we make of Messalina’s behavior? She, at first, made her husband a cuckold in private, as is the common use; but, bringing her business about with too much ease, by reason of her husband’s stupidity, she soon scorned that way, and presently fell to making open love, to own her lovers, and to favor and entertain

them in the sight of all: she would make him know and see how she used him. This animal, not to be roused with all this, and rendering her pleasures dull and flat by his too stupid facility, by which he seemed to authorize and make them lawful; what does she? Being the wife of a living and healthful emperor, and at Rome, the theatre of the world, in the face of the sun, and with solemn ceremony, and to Silius, who had long before enjoyed her, she publicly marries herself one day that her husband was gone out of the city. Does it not seem as if she was going to become chaste by her husband’s negligence? or that she sought another husband who might sharpen her appetite by his jealousy, and who by watching should incite her? But the first difficulty she met with was also the last: this beast suddenly roused; these sleepy, sluggish sort of men are often the most dangerous: I have found by experience that this extreme toleration, when it comes to dissolve, produces the most severe revenge; for taking fire on a sudden, anger and fury being combined in one, discharge their utmost force at the first onset:—“He gives full reins to the fury:”

he put her to death, and with her a great number of those with whom she had intelligence, and even one of them who could not help it, and whom she had caused to be forced to her bed with scourges.

What Virgil says of Venus and Vulcan, Lucretius had better expressed of a stolen enjoyment betwixt her and Mars:—

“Mars, the god of wars, who controls the cruel tasks of war, often reclines on thy bosom, and greedily drinks love at both his eyes, vanquished by the eternal wound of love: and his breath, as he reclines, hangs on thy lips; bending thy head over him as he lies upon thy sacred person, pour forth sweet and persuasive words.”

When I ruminate on this rejicit, pascit, inhians, molli, fovet, medullas, labefacta, pendet, percurrit, and that noble circumfusa, mother of the pretty infusus; I disdain those little quibbles and verbal allusions that have since sprung up. Those worthy people stood in need of no subtlety to disguise their meaning; their language is downright, and full of

natural and continued vigor; they are all epigram; not only the tail, but the head, body, and feet. There is nothing forced, nothing languishing, but everything keeps the same pace:—“The whole contexture is manly; they don’t occupy themselves with little flowers of rhetoric.”

’Tis not a soft eloquence, and without offence only; ’tis nervous and solid, that does not so much please, as it fills and ravishes the greatest minds. When I see these brave forms of expression, so lively, so profound, I do not say that ’tis well said, but well thought. ’Tis the sprightliness of the imagination that swells and elevates the words:—

“The heart makes the man eloquent.”

Our people call language, judgment, and fine words, full conceptions. This painting is not so much carried on by dexterity of hand as by having the object more vividly imprinted in the soul. Gallus speaks simply because he conceives simply: Horace does not content himself with a superficial expression; that

would betray him; he sees farther and more clearly into things; his mind breaks into and rummages all the magazine of words and figures wherewith to express himself, and he must have them more than ordinary, because his conception is so. Plutarch says that he sees the Latin tongue by the things: ’tis here the same: the sense illuminates and produces the words, no more words of air, but of flesh and bone; they signify more than they say. Moreover, those who are not well skilled in a language present some image of this; for in Italy I said whatever I had a mind to in common discourse, but in more serious talk, I durst not have trusted myself with an idiom that I could not wind and turn out of its ordinary pace; I would have a power of introducing something of my own.The handling and utterance of fine wits is that which sets off language; not so much by innovating it, as by putting it to more vigorous and various services, and straining, bending, and adapting it to them. They do not create words, but they enrich their own, and give them weight and signification by the uses they put them to, and teach them unwonted

motions, but withal ingeniously and discreetly. And how little this talent is given to all is manifest by the many French scribblers of this age: they are bold and proud enough not to follow the common road, but want of invention and discretion ruins them; there is nothing seen in their writings but a wretched affectation of a strange new style, with cold and absurd disguises, which, instead of elevating, depress the matter: provided they can but trick themselves out with new words, they care not what they signify; and to bring in a new word by the head and shoulders, they leave the old one, very often more sinewy and significant than the other.There is stuff enough in our language, but there is a defect in cutting out: for there is nothing that might not be made out of our terms of hunting and war, which is a fruitful soil to borrow from; and forms of speaking, like herbs, improve and grow stronger by being transplanted. I find it sufficiently abundant, but not sufficiently pliable and vigorous; it commonly quails under a powerful conception; if you would maintain the dignity of your style, you will often perceive

it to flag and languish under you, and there Latin steps in to its relief, as Greek does to others. Of some of these words I have just picked out we do not so easily discern the energy, by reason that the frequent use of them has in some sort abased their beauty, and rendered it common; as in our ordinary language there are many excellent phrases and metaphors to be met with, of which the beauty is withered by age, and the color is sullied by too common handling; but that nothing lessens the relish to an understanding man, nor does it derogate from the glory of those ancient authors who, ’tis likely, first brought those words into that lustre.The sciences treat of things too refinedly, after an artificial, very different from the common and natural, way. My page makes love, and understands it; but read to him Leo Hebraeus and Ficinus, where they speak of love, its thoughts and actions, he understands it not. I do not find in Aristotle most of my ordinary motions; they are there covered and disguised in another robe for the use of the schools. God speed them! were I of the trade, I would as much naturalize art as they

artificialize nature. Let us let Bembo and Equicola alone.When I write, I can very well spare both the company and the remembrance of books, lest they should interrupt my progress; and also, in truth, the best authors too much humble and discourage me: I am very much of the painter’s mind, who, having represented cocks most wretchedly ill, charged all his boys not to suffer any natural cock to come into his shop; and had rather need to give myself a little lustre, of the invention of Antigenides the musician, who, when he was asked to sing or play, took care beforehand that the auditory should, either before or after, be satiated with some other ill musicians. But I can hardly be without Plutarch; he is so universal and so full, that upon all occasions, and what extravagant subject soever you take in hand, he will still be at your elbow, and hold out to you a liberal and not to be exhausted hand of riches and embellishments. It vexes me that he is so exposed to be the spoil of those who are conversant with him: I can scarce cast an eye upon him but I purloin either a leg or a wing.